I remember the years 2008 and 2009 as a period when many art institutions across Europe dedicated major exhibitions to “the changing planet” and in particular to the effects that global warming, pollution, land erosion and other sources of environmental degradation were having on the living world. At the time, raising awareness about the unfolding eco-carnage was a theme like many others for artists. Their works were visually arresting but most of them never stepped out of museum and gallery spaces.

Tools for Action, Red Line Barricade, COP21 protest, Paris 2015. Courtesy Tools for Action Foundation. Photo: Artúr van Balen

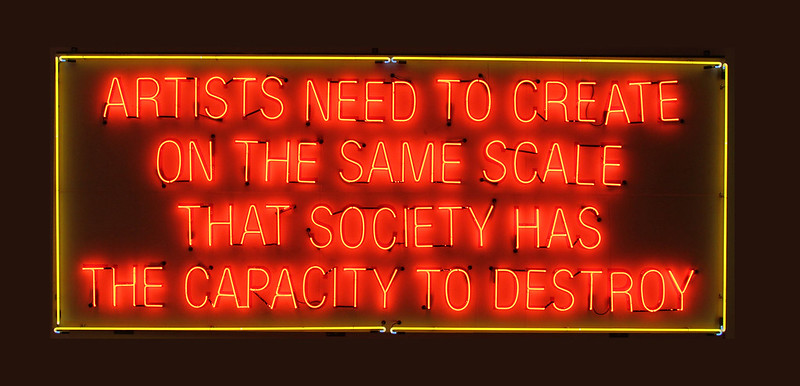

Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio, Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy, 2006/2021 © Metabolic Studio

Today, however, it is hard to look at the environmental emergency as if it were an artistic theme like any other. Legislations, corporate promises and governmental efforts to “drive down emissions” are too weak to prevent planetary breakdown. Most are not even implemented anyway. This is why more and more artists are now putting their practice and skills directly at the service of the climate justice movement.

Flood Tide of Resistance, an exhibition that opens at NeMe in Limassol (Cyprus) on Friday 7 October, presents the work of artists who actively support the climate justice movement. The artists selected by Oliver Ressler cover many grounds, deploy different strategies and come from various parts of the world. Their tactics and degrees of involvement vary: Tools for Actions creates playful tools that climate activists can appropriate and use; Tiago de Aragão documented and participated in the mobilisations of indigenous communities against the destruction of their livelihoods; the members of No Grandi Navi have campaigned with vigour against cruise-ship tourism in Venice, etc.

The show at NeMe is a spin-off of Overground Resistance which opened last year at Q21 in Vienna. Both shows have the same vigour and messages but along with the projects that took place on land, visitors of Flood Tide of Resistance will also discover activism that takes place at sea.

I caught up with artist and filmmaker Oliver Ressler as he was preparing the exhibition to ask him a few questions about climate justice, new forms of civil disobedience and artistic engagement:

Tiago de Aragao, Entre Parentes, 2018

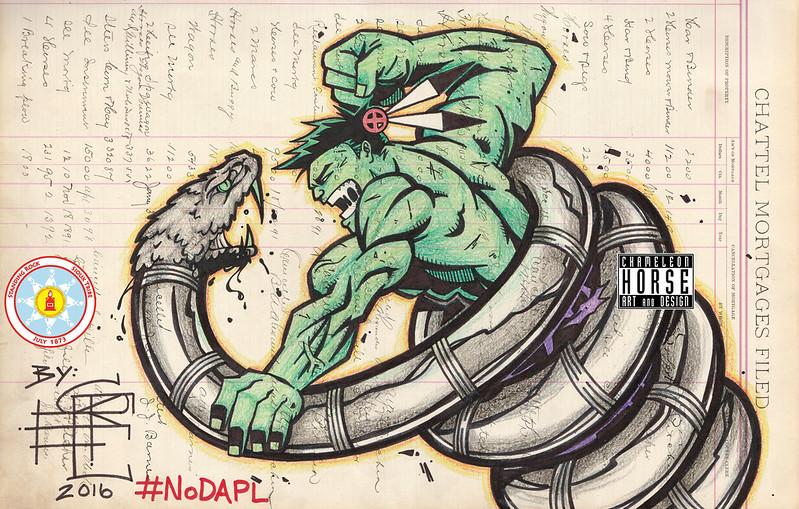

Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III, #NoDAPL, 2016

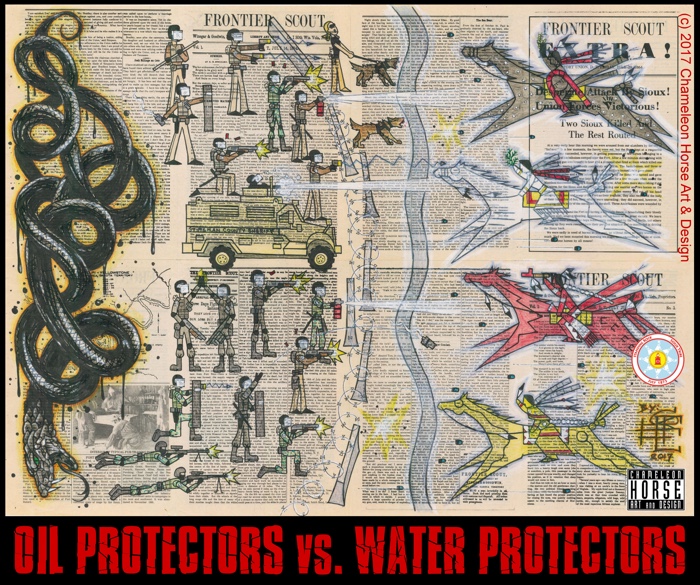

Gilbert Kills Pretty Enemy III, Water Protectors VS. Oil Protectors, 2018

Hi Oliver! I found it interesting that instead of the usual show about climate movements, the exhibition explores the climate justice movements. Could you tell us about the distinction?

I think in the Global North many people think, the problem with the climate is primarily too much carbon in the atmosphere, and therefore we have to achieve decarbonization. While it is necessary to achieve decarbonization, this is not enough. We also need to talk about climate justice, to compensate the Global South which in a historical perspective contributed much less to global warming, while facing the most severe, most brutal consequences of climate breakdown. A change in our perspective is important: In regard to climate breakdown, the North is the debtor, and it has to start accepting this inconvenient role and start transferring huge amounts of money as compensation for the damages that occur due to extreme weather events; money, which will also be needed to pay for adaptation measures and decarbonizing the South.

Oliver Ressler, Barricade Cultures of the Future, 2021

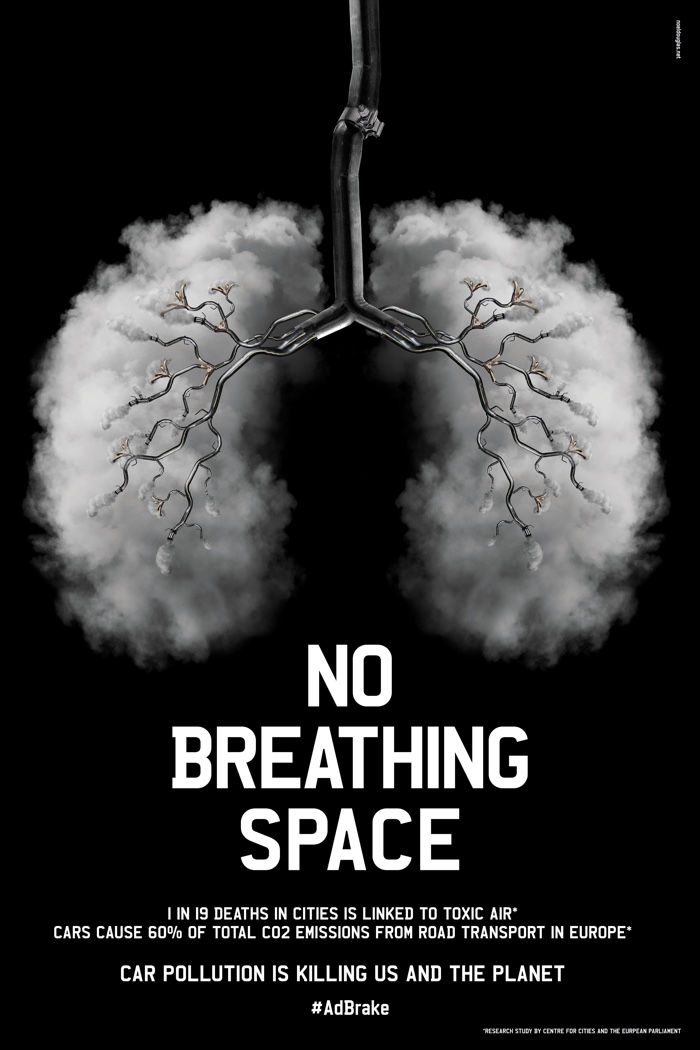

Noel Douglas, No Breathing Space, 2020

How important is it for artists to collaborate with NGOs, local activists, indigenous communities and other actors of the climate justice movement?

If you care about the future of life on the planet, you have several possibilities to continue working as an artist, doing work in relation to and in collaboration with protagonists of progressive social movements. And I’m afraid a classical studio practice is becoming more and more cynical and irrelevant… Already now we see some artists taking on the responsibility of documenting actions and creating tools that can be used to spread the word and broaden anti-extraction activities. Others participate in shaping the visual appearance of groups, creating tools that can be used in direct action. Some collaborate in designing the choreography of mass actions of civil disobedience. Others establish new networks of collaboration and support indigenous or under-privileged communities in sacrifice zones. I believe all of these are very meaningful activities.

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner & Aka Niviâna, Rise: From One Island to Another, 2018

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner & Aka Niviâna, Rise: From One Island to Another, 2018

The exhibition you curated for frei_raum Q21 exhibition space was titled Overground Resistance. The show you curated for NeMe is Flood Tide of Resistance. If I understand correctly, it is more focused on the sea. How did you go from a show that looks at climate justice resistance on land to one that looks at marine environments?

It would be boring to repeat exactly the same show I already did last year. In addition to the works that were presented at Museumsquartier in Vienna last year, at NeMe Arts Centre we also include art works focusing on resistance specific to the sea, connecting my curatorial research to a research project NeMe was already involved in. It recognizes the importance of the sea as a space where activity required for the perpetuation of the neoliberal economy happens. Commodities are moved around the planet in crude oil-burning container ships, but the sea is also an extraction site for raw materials. Right now, corporations and states are competing for control of the deep-sea mining sites of the future. Whether or not this new round of accumulation, exploitation and destruction will become reality will depend on the capacity of our movements to grow and block and intervene.

Comitato No Grandi Navi, 2015/2016

Comitato No Grandi Navi, 2015/2016

Comitato No Grandi Navi, 2015/2016

Comitato No Grandi Navi, 2015/2016

How do activists make the defence of the sea more urgent and visible when, as is often the case, it’s easier for many of us to relate to where we live (the land) and less so to what’s out there in the vast sea?

Many people live in coastal or seaboard areas; for those people it’s a natural thing to care about the sea, and maybe also expand direct action to the sea. For years, No Grandi Navi in Venice have been trying to stop cruise ships entering the laguna. Using their small boats, they obstruct the large cruisers directly with their bodies. Their actions keep these huge ships from landing, and also create a new kind of imagery, which gets distributed by media, making the issue more visible to a wider public. The struggles against mass tourism, against climate breakdown and against the destruction of the laguna converge in these amazing actions. After years of struggles, at the very least, No Grandi Navi succeeded in hindering the cruise ships from entering the laguna.

In his book How To Blow Up a Pipeline, Andreas Malm calls for the climate movement to escalate its tactics in the face of ecological collapse. The situation is so dire and the absence of an adequate response is so depressing that we don’t have time for peaceful protests anymore. Is this something you would agree with? Is it ever acceptable to resort to sabotage and “controlled” violence if the cause is just, urgent and ignored after decades of quiet protests and other peaceful tactics?

Andreas Malm explains quite clearly that at a time when ongoing business-as-usual means more and more new extraction projects that vandalize our climate, it should be the responsibility of states to dismantle the climate-wrecking industry and to expropriate the owners and shareholders. As we know, there is not a single state doing this. Property rights seem untouchable. Therefore, whether we like it or not, it appears that our only way to expropriate the climate wreckers is to do it ourselves, through sabotage or by destroying their machines. Such actions have been happening for decades; e.g., the Ogoni in their fight against Shell’s murderous oil extraction have a long record of destroying pipelines. It is absolutely clear that the non-action of states will lead to a global wave of sabotage on a scale the planet has never seen before. It will happen on that scale as soon as people sense that this is the only chance to prevent further disasters.

Thanks Oliver!

Exhibition views and images of the artworks in the show:

Flood Tide of Resistance. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Noel Douglas

Flood Tide of Resistance. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Noel Douglas

Flood Tide of Resistance. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Noel Douglas

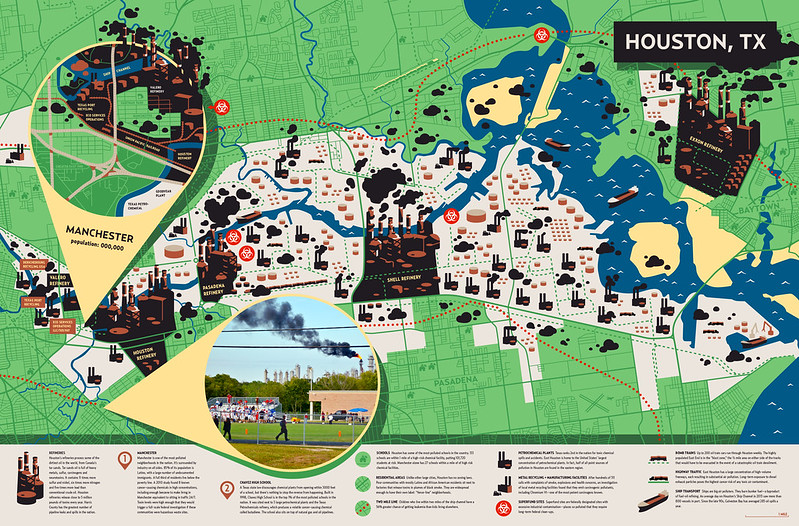

The Natural History Museum, Houston Map, poster, 2016

Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas, 2020

Tools for Action, Red Line Barricade, COP21 protest, Paris 2015. Courtesy Tools for Action Foundation. Photo: Artúr van Balen

Noel Douglas, No Breathing Space, 2020

Flood Tide of Resistance, curated by Oliver Ressler, opens at NeMe in Limassol, Cyprus, on Friday, 7 October 2022, 7:30pm. The show is open until 4 November 2022.

The seminar Flood Tide of Resistance will take place on Saturday, 8 October 2022, 6:30pm.

Related stories: How to Blow Up a Pipeline. Learning to Fight in a World on Fire, Disobedience Archive (The Republic), Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century, etc.