[ad_1]

PARIS — War in Europe, a world wide pandemic, and rapid technological change that altered people’s relationships to perform, family, and modern society. This is the backdrop against which the art historic exhibition Pioneers at the Musée du Luxembourg aims to rewrite the roles that girls played in the city’s avant-garde artwork movements of the 1920s. Featuring is effective in different mediums by far more than 45 artists, the exhibition destinations a unique emphasis on women of all ages who — by means of portray, sculpture, music, dance, and creating — challenged and subverted traditional norms of gender presentation, sexuality, motherhood, and race.

The show’s lead curator, Camille Morineau, is a pioneer in the French artwork planet in her possess right. She’s the director of Conscious (Archives of Ladies Artists, Investigate and Exhibitions), a nonprofit she founded in 2014 to “rewrite the history of art” by putting “women on the same stage as their male counterparts.”

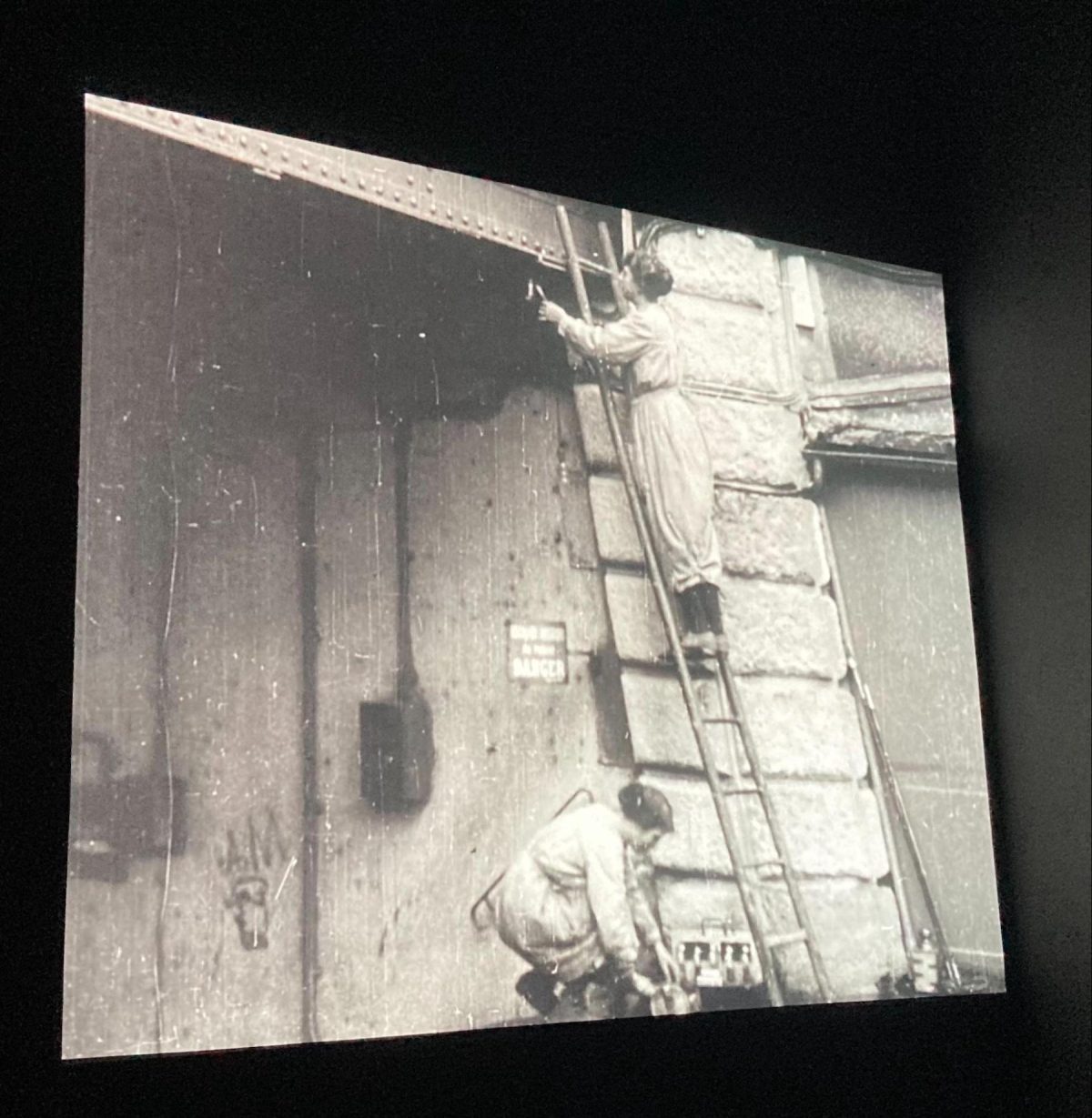

The exhibition’s to start with illustrations or photos come from Earth War I-era archival footage. “In France as well, females changed gentlemen in traditional occupations,” we go through in advance of seeing a short silent film of women functioning manufacturing facility machines, conducting public transportation, and retaining rooftop heating programs. Through the next seven rooms Morineau proceeds to emphasize economic and social evolution as foundational to, and intertwined with, female creative exploration.

A prime illustration is Josephine Baker, who located inventive and business results after transferring to Paris in 1925, at the age of 19, to escape segregation in her indigenous United States. She quickly grew to become “one of the most effective paid out artists in Europe” by capitalizing on her attractiveness as a cabaret performer to develop what we would contact currently her “brand.” A single screen files her garçonne look and bohemian way of living along with the menu for a luxury cafe she opened, the to start with edition of a magazine she introduced, and the packaging of Bakerfix, element of her cosmetics line. But Morineau glosses over (or probably leaves it to us to infer) a far more complicated knowledge of the racial dynamics concerned in Baker’s unparalleled results. As journalist Rokyaha Diallo has pointed out, Baker’s act “was developed to depict a stereotypical eyesight of Africa that indirectly celebrated the colonial intention and racist notions of white superiority.”

In other places, Morineau asserts that embracing commercially feasible forms of expression (e.g., fashion, dolls, set design) permitted creators this sort of as Marie Vassilieff and Sarah Lipska to generate the monetary independence required for the enhancement of their artwork. For other people, like the Polish-born Stefania Lazarska, source-chain issues and resources shortages introduced about by the Second Earth War would put an close to their inventive entrepreneurship.

I located myself wishing that Morineau would have drawn higher parallels involving the economical struggles of girls artists in 1920s Paris and individuals that persist in up to date France and in other places. In 2020 Bruno Racine, a former president of the Centre Pompidou museum (exactly where Morineau also worked as a curator) and a present-day board member of A.W.A.R.E., authored an official federal government report on the standing of the country’s visual artists and authors. “The median all round personal money of visible artists is €10,000 for every 12 months for women,” the report states, when also noting that throughout all arts sectors, the median profits gap between guys and women is about -25 per cent.

But Morineau is extra fascinated in how modern identification politics are embedded in women’s inventive production from a century in the past. These issues materialize all through a series of rooms in which the feminine system is disrobed, portrayed via multiple lenses (motherhood, feminine friendship, ageing, sapphic wish), and re-clothed in a way that queers gender id and presentation. The self-taught Suzanne Valadon’s 1923 oil portray “La Chambre Bleue,” of a lady lounging in striped pajamas, issues similarly composed, eroticizing photographs by her male contemporaries. Chana Orloff’s bronze sculpture “Maternité couchée,” from the exact same calendar year, is an aesthetic exploration of the intimate nonetheless unglamorous act of breastfeeding.

Mornineau devotes an total area to the historical concept of the “third gender,” an elastic term that encompasses cross-dressing, homosexuality, female men, and masculine women of all ages. A person of the most striking examples is the writer, activist, and photographer Claude Cahun, who wrote in 1930 that, “Neutral is the only gender that always fits me.” A collection of her black and white, cross-dressing self-portraits challenge each bravado and a nuanced grasp of what it signifies to expose a self that quite a few men and women at the time, and now, would prefer keep on being hidden. These pictures take on an even better significance in the context of France’s modern presidential election, and the homophobic and transphobic statements of various candidates.

The exhibition finishes with a nod to yet another well timed problem: variety, specifically the illustration of aesthetics, cultures, and bodies that are not endemic to Western Europe. Morineau tries to show that (wealthy, privileged) women of all ages artists were “curious and open to other cultures” since they had been “on the periphery of a environment in which they preferred to be in the middle.” Among these functions are Lucie Cousturier’s watercolor portraits, this kind of as “Nègre écrivant,” from her 1921 govt-sponsored trip to West Africa, a tradition ongoing by the ethnographic sculptor Anna Quinquaud (“Portrait d’une jeune négresse,” “Chef foulah,” both of those 1930) — representations that Morineau qualifies with the unspecific expression “non-stereotyping.”

Amrita Sher-Gil’s 1934 “Autoportrait en Tahitienne” (a reaction to Paul Gaugin’s Tahitian paintings) and one of Tarsila do Amaral’s preparatory ink drawings for her landmark 1928 portray “Abaporu,” impressed by her native Brazil, start to shift beyond Eurocentrism. Despite these noteworthy inclusions, I remaining the exhibition’s ultimate place sensation that Mornieau had ignored a far more nuanced interpretation of art background: 1 in which the peoples indigenous to Africa and the Americas depicted are robbed of the ability to tell, to exhibit, to interpret their very own tales.

Pioneers carries on at the Musée du Luxembourg (19 Rue de Vaugirard, Paris, France) by July 10. The exhibition was curated by Camille Morineau, Heritage Curator and director of Archives of Females Artists, Research and Exhibitions, with associate curator Lucia Pesapane.

[ad_2]

Resource website link